PROJECTS & STORIES | #Journeys in the Giorgetti Archive

#Journeys in the Giorgetti Archive Jacques Couelle

by Cristiana Colli

An ochre folder, Giorgetti embossing, red block lettering. Meet Jacques Couelle and the wonderful story of dialogue between savoir-faire and visionary thinking, with detailed reports, sketches, notes and a few personal jottings as testimony.

It’s 14 March 1962. In Olbia, appearing before a notary, Mario Altea, Karim Aga Khan, Patrick Guinness, Felix Bigio, André Ardoin, John Duncan Miller and René Podbielski officially established Consorzio Costa Smeralda. Aga Khan, along with the wealthiest families in Europe (from the Rothschilds to the Fürstenbergs), drafted an ambitious plan for the Costa Smeralda (literally, ‘Emerald Coast’), an astonishingly beautiful no man’s land that still lacked roads, water and electricity.

His vision was as crystal clear as the sea that had so enchanted him: this strip of northern Sardinia would be the European Caribbean, just a onehour flight away from London and Paris.

At the time, Olbia was one of the poorest cities on the island: its port was partially destroyed, the airport closed, the road to Arzachena still unpaved, Gallura an isolated enclave. It was a once-in-a-lifetime chance to change the destiny of the area, to redraw the scale of desires somewhere between residence and experience, to create a resort archetype made of the landscape, amenities and hospitality. The imposing size of the project (and the investment), along with the lack of urban planning laws, motivated Aga Khan to devise a system of rules of his own. So, he formed an architectural committee composed of Luigi Vietti, Jacques Couelle and Michele Busiri Vici, which then defined where and how to build, starting with strict requirements: the search for a harmonious relationship between architecture and nature, the connection between spaces and panoramic views of the gulf.

Good intentions and a lively debate in the authoritative media outlets of the 1970s followed, where the Costa Smeralda model questioned the idea of new buildings and settlements that lack historical references.

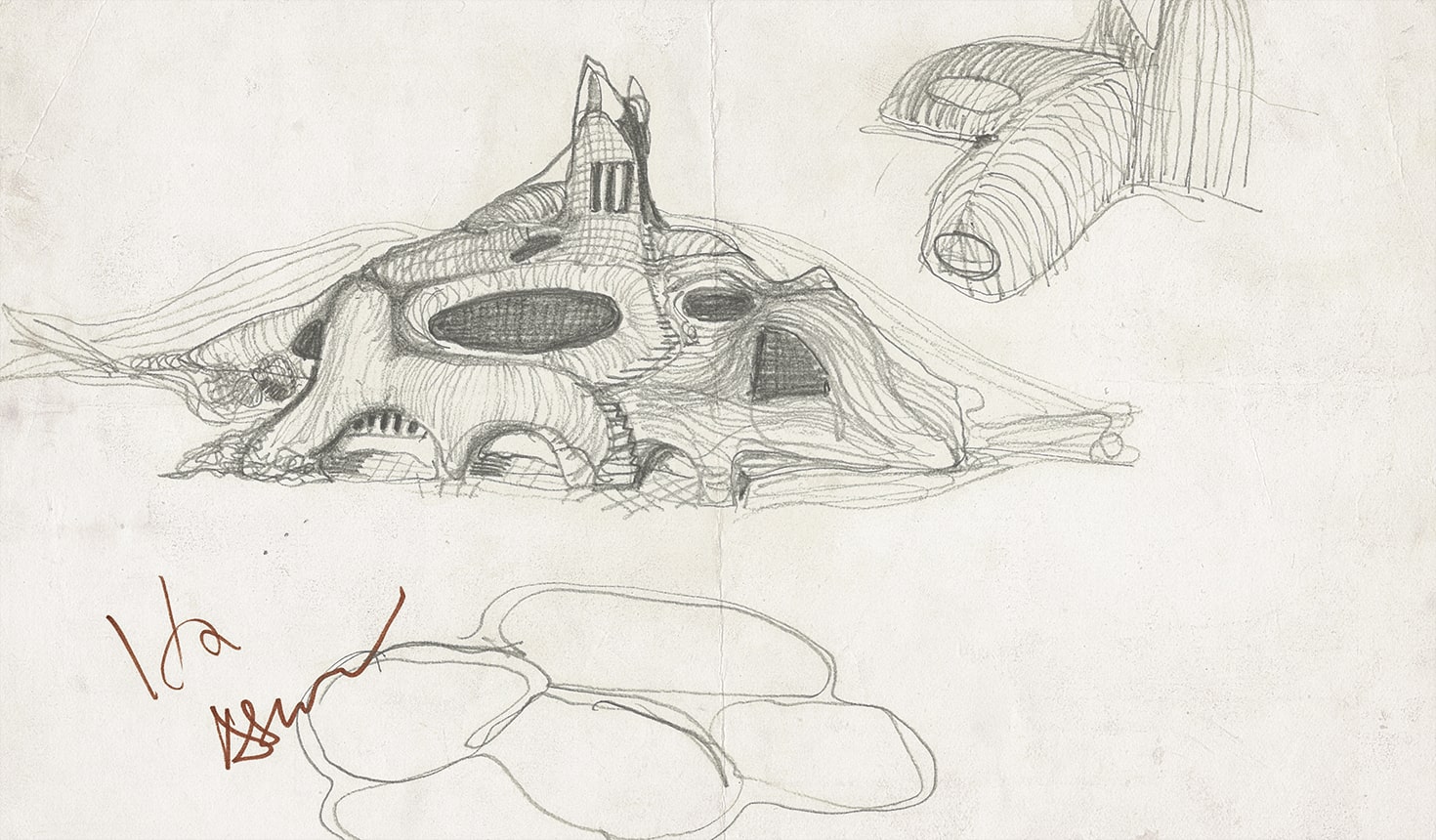

The area would soon be turned into one enormous construction site, erecting houses, hotels, and infrastructure, and Jacques Couelle would become one of the stars of the transformation. Couelle can be credited with the rediscovery of the intimate, ancestral relationship that binds man to his environment through organic forms, soft curves and rounded lines. His work took the shape of intersection and dialogue between architecture and sculpture, and his experiments with original, identity-generating materials (granite, wood, lime, iron wire) were often interpreted side-by-side with local craftsmen.

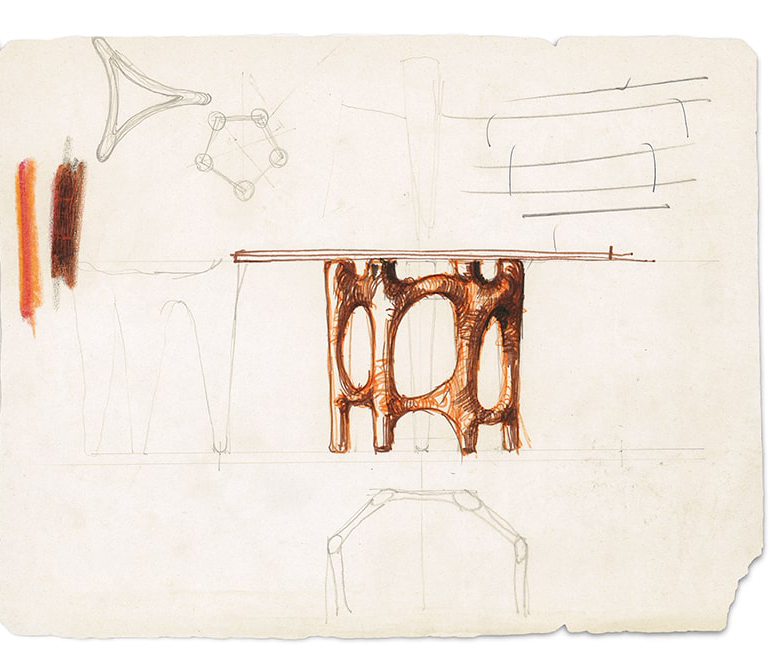

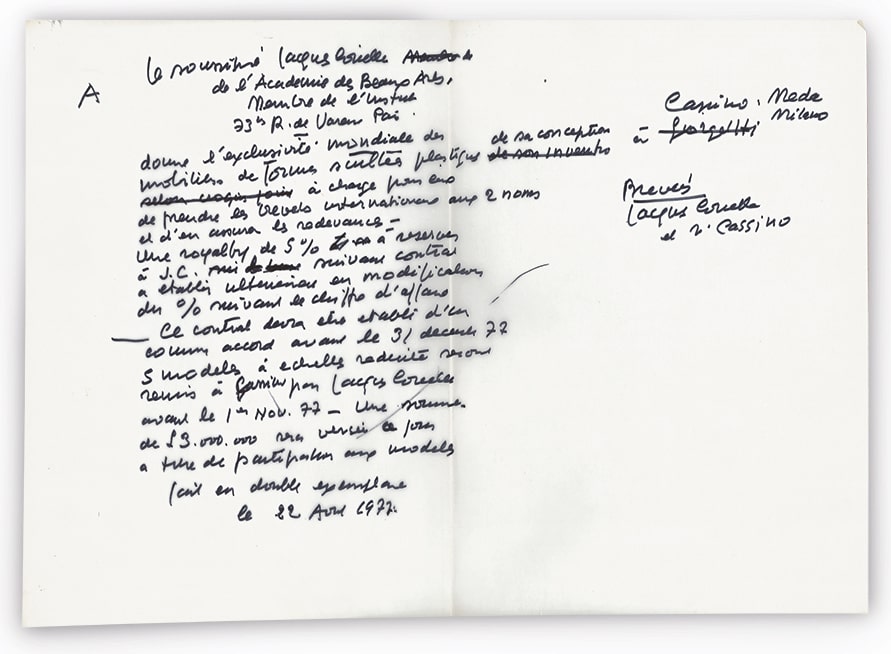

It was 30 November 1977 when Couelle—the architectsculptor, the anarchitect as Jacques Prévert had defined him, the eccentric artist friend of Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí who had been awarded the French Legion of Honour for artistic merit—called Meda. He reached out to Giorgetti for an important yet difficult task that required extraordinary skill. That was clear from the start. The dialogue was with Umberto Asnago, the head of the Design Department and a designer himself, one of those extraordinary figures who defined Italian manufacturing and incremental innovation in the districts.

In the letters sent between Meda and Paris, Couelle asked to verify the feasibility of a bold, challenging project: Asnago's reports give us the sense that the construction of a granite top with a spiral and components in tin sheet metal would be yet another opportunity for the skilled workers involved to try their hand at entirely new solutions.

Those celebrated designs would ensure that this important, complex project had a special fate, turning it into one of the most iconic places in the world: Hotel Cala di Volpe, a destination with the look of a traditional Mediterranean fishing village on the outside, defined by modern architecture on the inside.